Your Cart is Empty

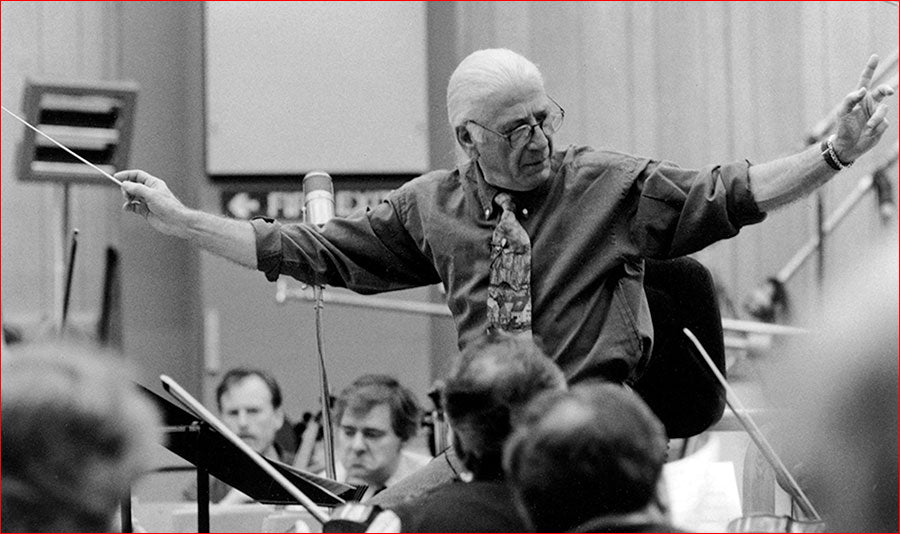

Recently, our own Selene Morrow had a chat with Emmy award-winning composer Inon Zur, who has worked on video game titles such as Baldur’s Gate II, Fallout, Dragon Age, Prince of Persia, and most recently, Syberia: The World Before and Starfield.

SM: Thank you for participating in this interview, Mr Zur. I hope things are well with you.

IZ: Thank you for inviting me, it’s my pleasure!

SM: To start things off, I would like to ask you about musical inspirations. Some of your favorite composers are some of ours as well, particularly Prokofiev, Bach and Jerry Goldsmith. Do you have a favorite score by Goldsmith? Would you say his style of music influenced yours? What about composers from more modern eras, or contemporaries?

IZ: Actually, I do have a couple favorite scores from Goldsmith. One of them is Basic Instinct, which is really one of his best scores because it is so twisted and sophisticated. And my other pick would be Planet of the Apes for his interesting use of percussion which is very compelling and innovative.

SM: Have you personally faced any obstacles early in your career, or even these days, where you felt like you had "unseen forces" working against you? In music, like in many industries, it does seem that "who you know" is important. Was there anyone who helped you early in your career to get your foot in the door?

IZ: Like with everything else in our world, and specifically when it comes to big projects, there’s a lot at stake, so obviously there is fierce competition. There is and always will be political forces that are present and influencing decisions and moves. I always try to distance myself from any affiliations with political sides or groups. I try to stay true to myself and concentrate my efforts into pure musical compositions and not deal with all the surrounding, in many cases, background noise which I choose to disregard.

One of the key people who opened the most doors for me was my former (now retired) agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment who got me started in the video games industry. He always championed me with great advice and mentoring. His contribution to my career is irreplaceable as a mentor.

SM: Do you have a favorite score that you've composed? Was there a project where everything just seemed to "click", and you felt like you were on the same wavelength as the director/lead game designer when it came to most or all of the creative process?

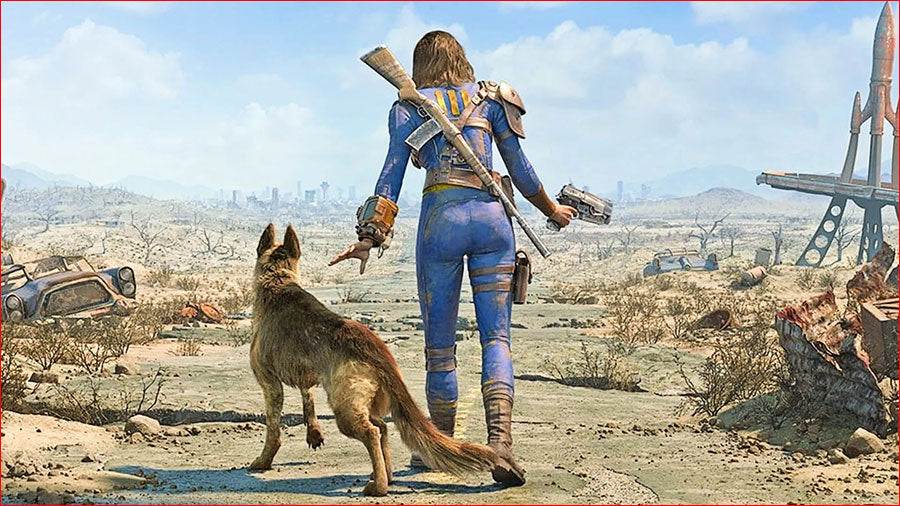

IZ: I must admit I have a very warm place in my heart for every project I’m working on since I’m trying to apply myself to every composition, no matter the specifics or type of project. Having said that, I believe that my work on Fallout and even more so Starfield, have inspired new and interesting musical ideas that I’m very proud of.

SM: Do you always tend to use live orchestras in the final version of productions? More and more composers these days rely on high-quality samples and VSTs, at least during the compositional phase, since they are becoming more and more realistic. Of course, it's a question of budget and it obviously varies depending on the budget of the production, but do you feel like you can reach approximately the same level of emotion/interpretative expression when you rely on VSTs/samples as opposed to an actual full-fledged orchestra? If not, do you envision that a time will soon arrive, when VST performances will feel like they are up to the task even in final production?

IZ: I strongly believe there is still no replacement for live orchestra, however some projects simply do not require a full orchestra. The orchestral sound is very specific and its employment should be based upon the needs of the project. Some projects are more sound design, modern, synthetic or ethnic heavy, so the use of the full symphony orchestra is not needed. I do believe that incorporating live performances in any score contributes greatly to the quality and emotional expression of each project. I am always trying to use live elements, whether it is soloist instruments or full orchestra, as long as the budget allows.

SM: On the topic of choosing instruments for recording sessions, I recall reading that a large part of the score for Fallout 4 was recorded with damaged instruments and objects such as garden furniture and oil drums, since those were items one might find in a post-apocalyptic world. How did you create the sound of a broken piano, for instance - were you able to locate an instrument that was in disrepair?

IZ: I did not use a broken piano, rather I used my own piano in a non-traditional way by recording the sounds of the piano strings when hammering or bowing, and also using the body of the piano as a percussion instrument and overall trying to exploit all the elements of the piano which were not traditionally meant to be played.

SM: You have mentioned that you enjoy playing video games (which is not always a given, even among video game composers!). What was the first game you ever played? Did any game you played have particularly memorable music - something that really stuck with you - and did that play a part in inspiring you to work in that field yourself?

IZ: One of the games where the music particularly struck a chord with me was Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune. I always love how Greg Edmonson builds the music with the game.

SM: We’d like to ask you some questions about your work on Dragon Age: Origins, a highly influential RPG from 2009 by BioWare. In our opinion, it’s some of the best music ever written for a video game, and it is our favorite of the Dragon Age games for which you provided a score. What was the process like writing the music for its sequel, Dragon Age II, as compared to working on the first game? Did you put a lot of pressure on yourself, when it came to following up a game like Dragon Age, which was so critically and commercially successful?

IZ: Dragon Age II was a different game in many ways. Compared to Dragon Age: Origins, Dragon Age II was a more intimate game with a story built on exile and the setting was very different. So I didn’t feel compelled to repeat myself or to compete with myself. I just chose different musical palletes. Obviously I did use elements from Origins when it came to themes but I orchestrated and used them in a different way according to the game’s setting.

SM: In the interim, you also composed the score for the Dragon Age: Origins expansion, Awakening. How did that experience fit in as far as your work on the Dragon Age franchise?

IZ: Awakening was quite a departure from Dragon Age: Origins and in fact during Awakening we started to build the preparation for Dragon Age II, it was darker and more ominous than Origins. Therefore I leant in a new direction, applying sound design elements that highlighted the darkness in the story.

SM: Since the visual setting of Dragon Age seems mainly inspired by Medieval Europe, I wanted to ask you how that influenced your approach when composing the score. As you surely know, what passes for “medieval” in people’s minds is often more accurately referred to as music from the Renaissance, and many composers opt to rely on a more traditional Romantic era orchestra (either in part or altogether) which is more evocative of an 1800s style, even when it comes to movies/games that are obviously set in a medieval-style world. Looking back on the score for Dragon Age: Origins, which inspiration era-wise would you say that you primarily relied upon?

IZ: I was definitely taking notes from the Renaissance era when it comes to instruments like the lute or other wooden flutes, however the way I used them can be attributed to the Romantic era, even modern film score. So I used these instruments but in a different orchestral stylistic setting.

SM: In composing for media, one is often faced with balancing diegetic (in-world) and non-diegetic (external, non-world) music. For instance, a tavern with bards would be an obvious place to rely upon diegetic music that is generated in the story and heard by the characters living inside the fictional world. Sometimes, the same piece can have both diegetic and non-diegetic elements. Your composition for Leliana’s Song at the party camp comes to mind, since her singing can be assumed to be heard by others, but the accompanying instruments are not actually in the scene, albeit still heard by the player. What are your thoughts about the balance between these two elements in general when it comes to the score for Dragon Age: Origins?

IZ: With Leliana’s Song the situation was unique because we tried to create a double impact, on one hand, creating a source music but on the other hand creating music that would affect the player emotionally. Therefore, the leading instruments are these vocals and the lute playing with Leliana are accompanied by the orchestra. In this way, we create the impression that this is something happening in the here and now in the scene but we add another depth with the orchestra.

SM: Dragon Age: Origins is highly branching, not just when looking at parts of the larger plot, but also within the context of individual conversations between the player and NPCs (non-player characters). Music in linear media such as movies has the benefit of being predictable. In other words, if two characters are having a friendly/angry/romantic moment, the music can be adapted to the flow of the scene. In games, this flow is difficult to predict, since the course of conversations and other events can vary between play-throughs and is based on player input. Did you find that you had to make certain scenes neutral/reserved in style, since you couldn’t be sure how the conversation would play out, and didn’t want to show any assumption/invisible hand with regard to what a player is expected to be feeling? And do you have some general thoughts surrounding this challenge, which is quite unique to composers that work in branching/interactive media?

IZ: You’re raising some great points on one of the main challenges scoring games - how to create a musical piece that will support and follow the player’s individual actions. My main technique is to ‘frame’ the scene and in musical terms that means creating a more neutral sound that poses a musical question mark to the player. In other words, the fate of the player’s next move will be dependent on his/her action but the music supports more of the questions rather than the answer.

SM: Prior to your work on the Dragon Age series, you also worked on Baldur’s Gate II, which is another beloved game series. Did any of this involve the original release, Shadows of Amn, or was it mostly (or all) related to the expansion, Throne of Bhaal? What was the experience like, especially when it came to cooperating/co-writing the music with Howard Drossin? Did you make a conscious effort to maintain a thematic/stylistic connection to the music for the main game, Shadows of Amn (which I believe had music by Drossin, as well as Michael Hoenig of Tangerine Dream fame)?

IZ: It was only Michael Hoenig. I listened to Michael’s score and took notes as we wanted to stay in the same realm. However, every project needs a score that is dictated by the story first and foremost. Throne of Bhaal was a different story in a different setting so we used an existing sound pallete from the world of Baldur’s Gate but propelled it with the different themed game and story.

SM: One of your most recent projects is Starfield - an upcoming action RPG by Bethesda Game Studios. We’ve listened to some of the score that you recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra (it’s quite brilliant, by the way) and feel like it’s going to be very interesting to hear in the context of the final game. How did this experience differ from your work on games in the past? Did you rely on any new tools/technology previously unavailable to you, and do you feel that your years of experience have made you a different composer than you once were, in terms of approaching ambitious projects of this sort? I was also wondering what it was like to work on this score with the London Symphony Orchestra. Did it have any special meaning to you, due to their past cooperation with John Williams on a great many movies, such as Star Wars, Superman, and Raiders of the Lost Ark?

IZ: For Starfield, more than any other project, I have brought all my previous experiences and background and leveraged them into a new musical journey. It’s like taking lots of pieces of knowledge, experiences and ideas, and creating a new picture with them. With Starfield I finally had the opportunity to combine all these elements that I’ve always wanted to create. The game’s concept of space adventure inspired a lot of musical ideas in me that in previous projects I did not have the opportunity to bring to life. Also, Starfield’s story is deeply philosophical which allowed me to deepen my musical thoughts to create something new and unique and I cannot wait to share the score with the fans.

SM: By way of a conclusion, I wanted to ask you if you have any other interesting projects coming up that admirers of your work should be on the lookout for.

IZ: As always there are a lot of exciting projects in development that I cannot discuss yet, but hopefully I will be able to reveal some of them in time.

SM: Thank you greatly for your time, Mr Zur. We’d love to reconnect again once Starfield has been released to talk about that in greater detail, as well as about anything else that you may be working on at that point.

IZ: My pleasure. Thank you for your interest and the great questions, I’d be delighted to speak with you again.